With Chi-Pan Chen, Yu-Hsin Wu, Jhi-Yi Liu, Pei-Chun Shih, Gang Yen, Chi-Min Tsai, Chun-Ta Chiu, Freya Chou, Daisy Li, Chih-Ming Feng, Leo Wang, Ku-Ming Chen and Chi-An Tsai

Every object assumes a name, a place, a value, and utilitarian or symbolic meaning. Much of a society‘s labor is spent keeping objects and their classifications pure and stable (above all, in the name of safety or cultural values). But before, underneath, and after this order, there is plenty of uncertainty and impurity. Antiquity-Like Rubbish Research & Development Syndicate, led by artist Yeh Wei-Li since 2010, is dedicated to this uncertainty and to the movement of things across boundaries.

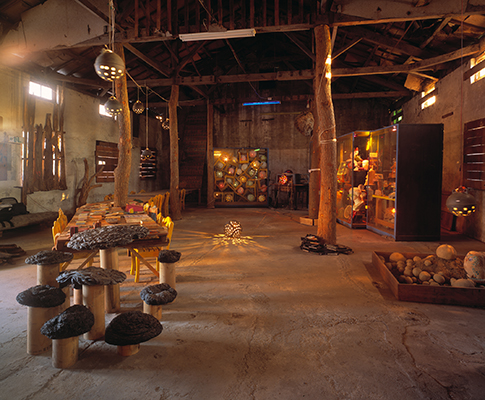

This process-oriented work began in 2010 with a concrete spatial renovation project in which sixteen artists collaborated, and has since materialized in different temporary collaborations involving various forms of production, reflection, and media. The project maps the processes and movements among the categories of “art,” “antiquity,” and “trash.” The precarious balance between these categories functions like a map that registers “transformation” in the order of society, whether this be devaluation and destruction in urban renewal, or value-production in commodity capitalism, or the quasi-magical production of “value” in art.

Each of these three categories delineates a class of objects beyond utility. “Trash” designates objects that have become value-less. Objects here literally “fall apart” and become “impure” and “undifferentiated,” that is, without clear borders—hence the affinity of trash with monstrosity. It is in this realm of hybridity that the project finds its materials: objects salvaged during spatial renovation projects, objects from illegal roadside dumping grounds, neighborhood construction sites, beaches, and riverbeds. Can such discarded debris be “elevated” and achieve the status of either “antiquity” or “art” through analysis, evaluation, and aesthetic judgment? Can it simultaneously challenge the hierarchy between trash and art—its connection, for instance, to the classifying and evaluating institutions of the museum, the market, or individual authorship, and its disconnection from everyday collective practice, life, and locality?

Wei-Li Yeh, born 1971 in Taiwan, lives and works in Taipei