with Wei-Li Yeh with Chi-Pan Chen, Yu-Hsin Wu, Jhi-Yi Liu, Pei-Chun Shih, Gang Yen, Chi-Min Tsai, Chun-Ta Chiu, Freya Chou, Daisy Li, Chih-Ming Feng, Leo Wang, Ku-Ming Chen, Chi-An Tsai, Wen-Chi Deng and Yu-Hong Chang

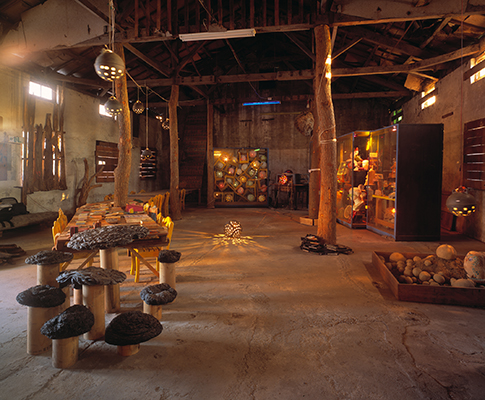

Yeh’s work at various times interrogates what happens at the margins of contemporary capitalist society. Places play a crucial role in this interrogation, whether they be the margins of the city, abandoned sites and ruins, places that are transforming and giving way to something new, or simply those places that are significant to the artist. It is in the crisis and disorder of the abandoned—in things caught halfway between trash and cultural artifact, and above all in everything that is discarded—that he finds the material for his dense narratives which ultimately crystallize in his photographic images.

The object in this series was found in 2005 in Wae Wu Yin, a former navy compound in the Taiwanese city of Kaohsiung. Shortly after, the compound was destroyed to make way for the city’s new opera house. The object is a painting depicting Emperor Go Jian, an ancient and historical figure, protagonist of popular legends, and approaching divinity. Living some 2300 years ago, Go Jian was the emperor of the Yue Kingdom and is best known for having been captured and made to serve his enemies in the Wu Kingdom for three years. While in captivity Emperor Go kept alive the humiliating memory of this catastrophic defeat by forcing himself to ingest a fragment of bitter venison gall bladder nightly, until he later took revenge and reclaimed the warring states of what we now know as China. The legend of Emperor Go Jian, who wanted to win back his lost empire, is widely used as a template for the Kuomintang’s fate and their claims on mainland China after they fled to Taiwan in the late 1940s. Indeed, paintings depicting Go Jian can still be found in many Taiwanese military installations today. It was just such a discarded painting that Yeh found in Kaoshiung.

Yeh took this painting to his home in Taipei and photographed its journey through different contexts, staging expressively quotidian scenes where the painting functions as mere backdrop. Along this eight-year journey which continues into the present, the painting naturally and superficially decomposes and gets reassembled, as if in an attempt to reconstruct the painting so it can be permanently archived before it finally disappears. Yeh constructs this journey as a different kind of homecoming—not as conquest and revenge, but as dispersal of a memory within a city, as a nomadic experience within the context of urban life and its struggles.

Wei-Li Yeh, born 1971 in Taiwan, lives and works in Taipei