The subject of this piece is the film A Brighter Summer Day (1991) by seminal Taiwanese director Edward Yang. Together with Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s City of Sadness, A Brighter Summer Day has become the main cinematic representation of Taiwan’s White Terror period (1949–1987). Set in Taipei from 1959 to 1961, the film is based on a real-life story: a schoolgirl’s murder by her boyfriend, considered the first juvenile murder case after 1949. With this film, Yang attempted to create a representation of a period in Taiwan’s history that, in his own words, is “deliberately ignored and forgotten”. He considered the actual murder an inevitable result of the societal structure and political environment, and he uses the incident as a narrative tool to describe its logic.

The central element of Teng’s work is a life-size sculpture depicting the final scene of the film. This scene is the culmination of a process of victimization: a girl being murdered, a murderer who is presented to us as the victim of circumstances. It is a scene of a dramatic and perverse dialectic logic, a so-called double bind: in the act of the murder the protagonist attempts to reclaim his agency from an environment that deprived him, but this attempt at breaking free ultimately turns into its opposite, a trap through which he ultimately falls prey to the structure. The presentation of the “scene” as a monument further raises the question of the politics of memory. Is there a similar trap or double bind in the logic of memory and historical narrative, in something that endorses history after the fact as inevitable? How much of the past can we figure out to support what to memorize? On the window behind the sculpture, we read the final words of the girl (Ming): “I am like this world. It will never change!”

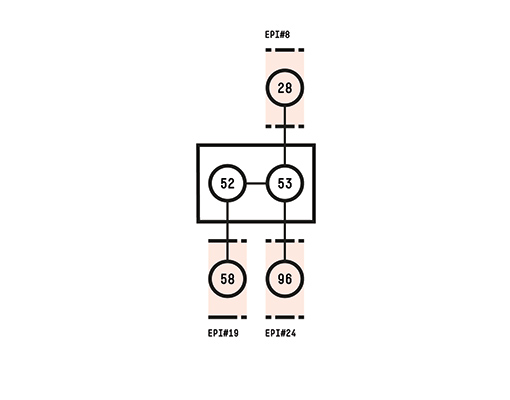

In addition to the sculpture there is a series of documents on display that analytically decompose the narrative into discrete actions, with the attempt to present the systemic interactions between all the actors. Teng’s diagrams are models to structurally understand how “inevitability” and “empathy” are building up in Yang’s film, and furthermore, to reflect on how structure and human agency are related in historical processes.

Teng Chao-Ming, born 1977 in Taiwan, lives and works in New York and Taipei